Elder Echo Hawk Connects Pawnee Indian Ancestors with Mormon Pioneers

Contributed By Sarah Harris, Church News staff writer

Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk, General Authority Seventy (left), talks about his great-grandfather (right) during his June 27 LDS Business College devotional address at the Assembly Hall on Temple Square.

Article Highlights

- The Lord wants us to hasten His work for both the living and the dead.

“We can know our ancestors, we can do their temple work, and this will add to our spiritual strength and our purpose in life.” —Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk of the Seventy

Related Links

Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk, General Authority Seventy, talked about a connection between his Pawnee Indian ancestors and the Mormon pioneers as he testified on June 27 of the spiritual blessings that come from doing temple work.

He began his remarks during his LDS Business College devotional by explaining the origin of his last name, which was given to his great-grandfather. The hawk is a symbol of bravery among the Pawnee people, and since his brave deeds were spoken of from one side of the village to the other, the elders of the tribe gave him the name Echo Hawk.

Elder Echo Hawk recounted the history of the Pawnee people, who in the 1800s lived in what we now call Nebraska and northern Kansas. In the winter of 1874, the United States government forced them to relocate to the Oklahoma Indian Territory.

“It is a painful history,” Elder Echo Hawk said. “Not only did the Pawnee people lose their homeland, they lost their way of life.”

The suffering of the Pawnee people carried on to future generations. But out of pain was eventually born promise, Elder Echo Hawk said. When he was 14 years old, two missionaries from the Church came into his home and taught his family.

“I have felt the Lord’s hand in my life as I have progressed through many years,” Elder Echo Hawk said.

He said history was made in 1990 when he was elected Idaho’s attorney general—the first state constitutional office to be held by an American Indian in U.S. history.

Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk, General Authority Seventy, gives his LDS Business College devotional address June 27 at the Assembly Hall on Temple Square. Photo by Sarah Harris.

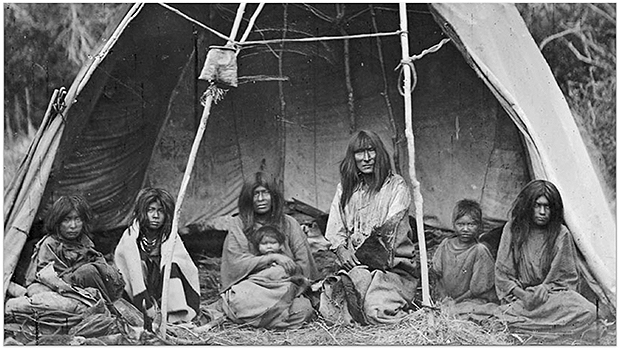

Elder Echo Hawk’s great-grandfather, who is the origin of the Echo Hawk name, is pictured in a photo taken by a photographer who traveled throughout Indian country taking pictures of Native Americans. Photo courtesy of Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk.

Elder Echo Hawk’s grandfather is pictured in a photo taken by the same photographer. These photos were obtained by a member of the Echo Hawk family at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., according to Elder Echo Hawk. Photo courtesy of Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk.

Elder Echo Hawk said because of this election, he was honored as a BYU Distinguished Alumni in 1992. In attendance at the Homecoming festivities where he received this award were Dale and Jill Kirkham, a young married couple who had a powerful spiritual prompting they needed to help Elder Echo Hawk with his family history work.

When the Kirkhams later expressed this, Elder Echo Hawk thanked them for their interest in helping him but explained that this was impossible because the Pawnee Indians were not a record-keeping people.

“But they had planted a feeling in my heart about my ancestors,” Elder Echo Hawk said.

A few months later, he was invited to speak at a large banquet in Nebraska. He felt that he should accept and agreed on the condition that an expert would take him on a tour of the Pawnee lands—the homeland of his people—while Elder Echo Hawk was there.

On this tour, he traveled to Genoa, Nebraska, and was taken to a historical marker that explained the story of the expulsion of the Pawnee people to Oklahoma.

“Interestingly, it was a dual historical monument because on the other side of this marker was the account of another people that the government had failed to protect—another people that had been expelled from their homes in Nauvoo, Illinois: the Mormons,” Elder Echo Hawk said. “Genoa, Nebraska, was a resupply point on the Mormon Trail.”

Determined to keep searching for records of his ancestors, Elder Echo Hawk continued his research in Oklahoma and eventually located some old census records of the Pawnee Indians. He said he found the Echo Hawk name on these records, as well as many interesting English names shared by well-known Mormons of the time, such as Brigham Young and Parley P. Pratt.

“Do you get a feeling about what was happening back in the mid-1800s at this resupply point where Pawnee Indians were located and Mormons were there?” Elder Echo Hawk asked.

With these census records, he and the Kirkhams were able to research and prepare the names of Elder Echo Hawk’s ancestors for the temple.

The Kirkhams later found in their own family history that Jill Kirkham’s great-great-grandmother traveled with the Mormon pioneers to Genoa, Nebraska, and lived there for 13 years. During this time, Elder Echo Hawk’s great-grandfather was born. He was 5 years old when Jill Kirkham left Genoa, Nebraska, at the age of 32.

“In my mind’s eye, I see Jill Kirkham’s great-great-grandmother holding my great-grandfather Echo Hawk,” Elder Echo Hawk said. “Something caused Jill Kirkham to have a spirit come to her that said, ‘You need to help.’ She was able to help, and this sacred work was done in the temple.”

Elder Echo Hawk testified that the Lord wants us to hasten His work for both the living and the dead.

“We can know our ancestors, we can do their temple work, and this will add to our spiritual strength and our purpose in life,” he said.

In his devotional address, Elder Echo Hawk spoke about how poor and destitute the Pawnee Indians were after being relocated to the Oklahoma Indian Territory. “One of the most free and independent and self-sustaining of all people on the face of the earth almost overnight became one of the most dependent people, forced to be confined on that small reservation and to subsist on handouts and rations that were issued by the United States government, and the people suffered,” he said. Photo courtesy of Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk.

The suffering of the Pawnee people continued through future generations, Elder Echo Hawk said. His father, second row from the front and fifth from the left, was taken from his parents and placed in a boarding school with the other young men pictured when he was 8 years old, in order to be “assimilated into the dominant culture.” Photo courtesy of Elder Larry J. Echo Hawk.

LDSBC students leave the Assembly Hall following Elder Echo Hawk’s devotional. Photo by Sarah Harris.

LDSBC students leave the Assembly Hall following Elder Echo Hawk’s devotional. Photo by Sarah Harris.